By T. Michele Walker

Herald-Tribune

Venice Theatre’s Stage II series presents a new production of David Lindsay-Abaire’s dark comedy about a woman struggling to hold on financially in South Boston

‘Good People’

Directed by Kelly Wynn Woodland.

David Lindsay-Abaire’s “Good People,” now playing at The Venice Theatre’s Stage II, is a play filled with contradictions; funny, frustrating and well constructed; played with sincerity, skill and warmth by a strong cast and directed with expertise by Kelly Wynn Woodland.

“Good People” does an outstanding job of posing the existential question of how much our circumstances define us and how much we define our circumstances. The question is not cleanly answered, but rather, a slippery slope of possibilities. Are we victims of fate or architects of our own destiny?

While not autobiographical, there’s an obvious personal connection for Lindsay-Abaire, who grew up in the poor, mostly Irish-Catholic blue-collar neighborhood of South Boston. Those roots are shared by Mike (a nuanced and well balanced performance by Paul Hutchison), a doctor who was smart and had the good fortune to escape to a more affluent, “lace curtain” existence across town in elegant Chestnut Hill.

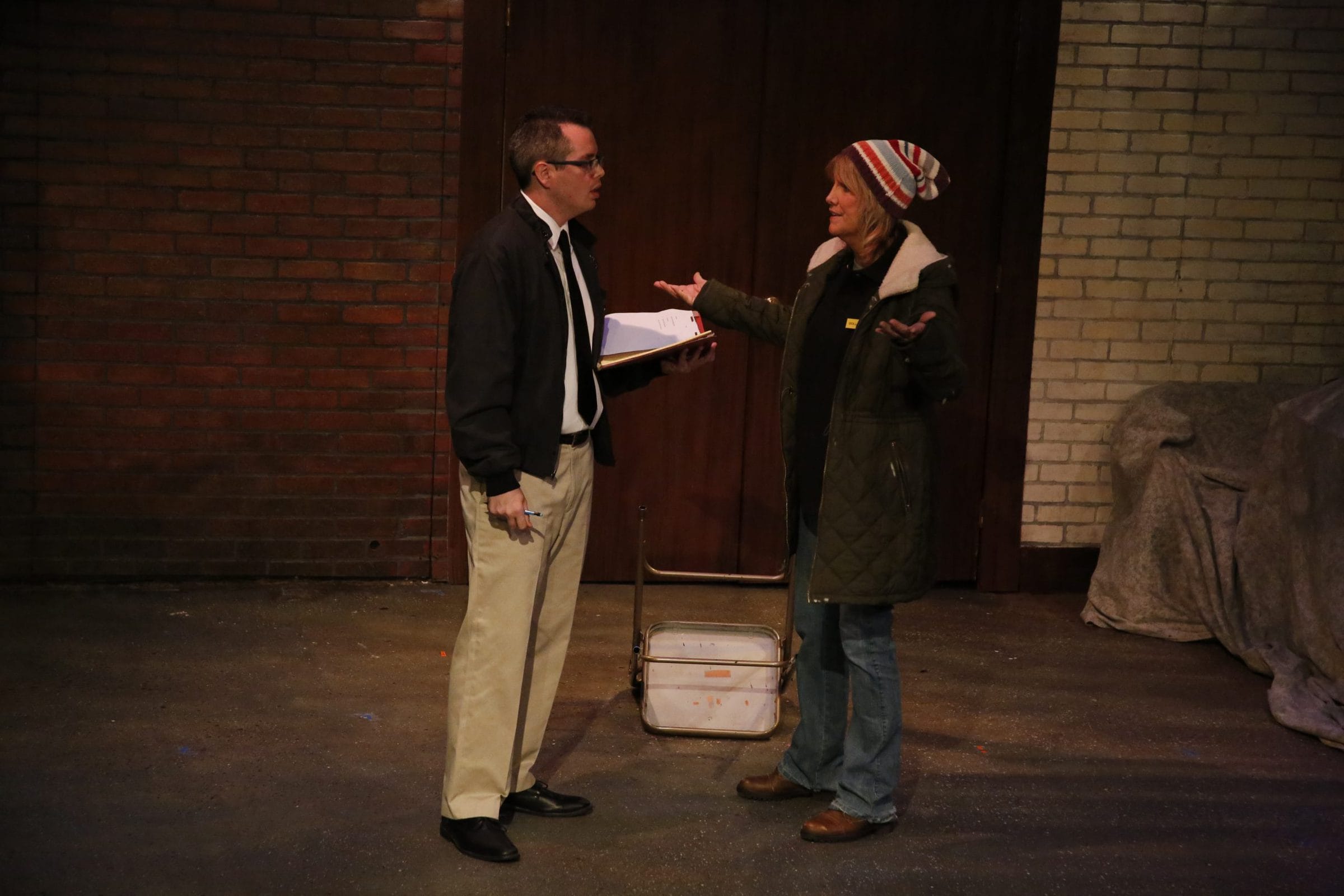

“Good People” opens in an alleyway behind the Dollar Store as Margie (a charming Nancy Denton), a single mother in her 50’s with a grown disabled daughter, and her boss, Stevie (appropriately underplayed by Jory Smith), the manager, have a meeting. It’s not been a good day for Margie. Let’s face it, it’s not been a good life. Late again for work because of caring for her special needs daughter, Stevie is under the gun by his boss to fire Margie. Margie, talking rapid fire, nervously trying at once to ingratiate and disarm Stevie, she fails at both and goes home jobless again. Through a gossiping friend, Margie hears that Mike, an old boyfriend, has become a successful doctor. He escaped the neighborhood cycle of poverty and she tracks him down in search of a job.

Denton’s Margie rides the rails in this story. Vulnerable and complex, it’s an understated performance in a well-plotted piece that seldom lets you see the twists coming. The opening scene with Stevie is finely executed and tight, setting up a nice pace for our production. In fact, each scene is directed with precision by Woodland with an expeditious set design by Sonja and Karin Carr, making good use of the small stage, allowing flow from scene to scene.

Margie’s friend, Jean (a strong Lynne Doyle) says repeatedly to Margie, “You’re too nice,” accusing Dottie (finely played character relief by Karen Kelly) of not being kind to Margie. But who is watching Margie’s special needs daughter each evening for little pay?

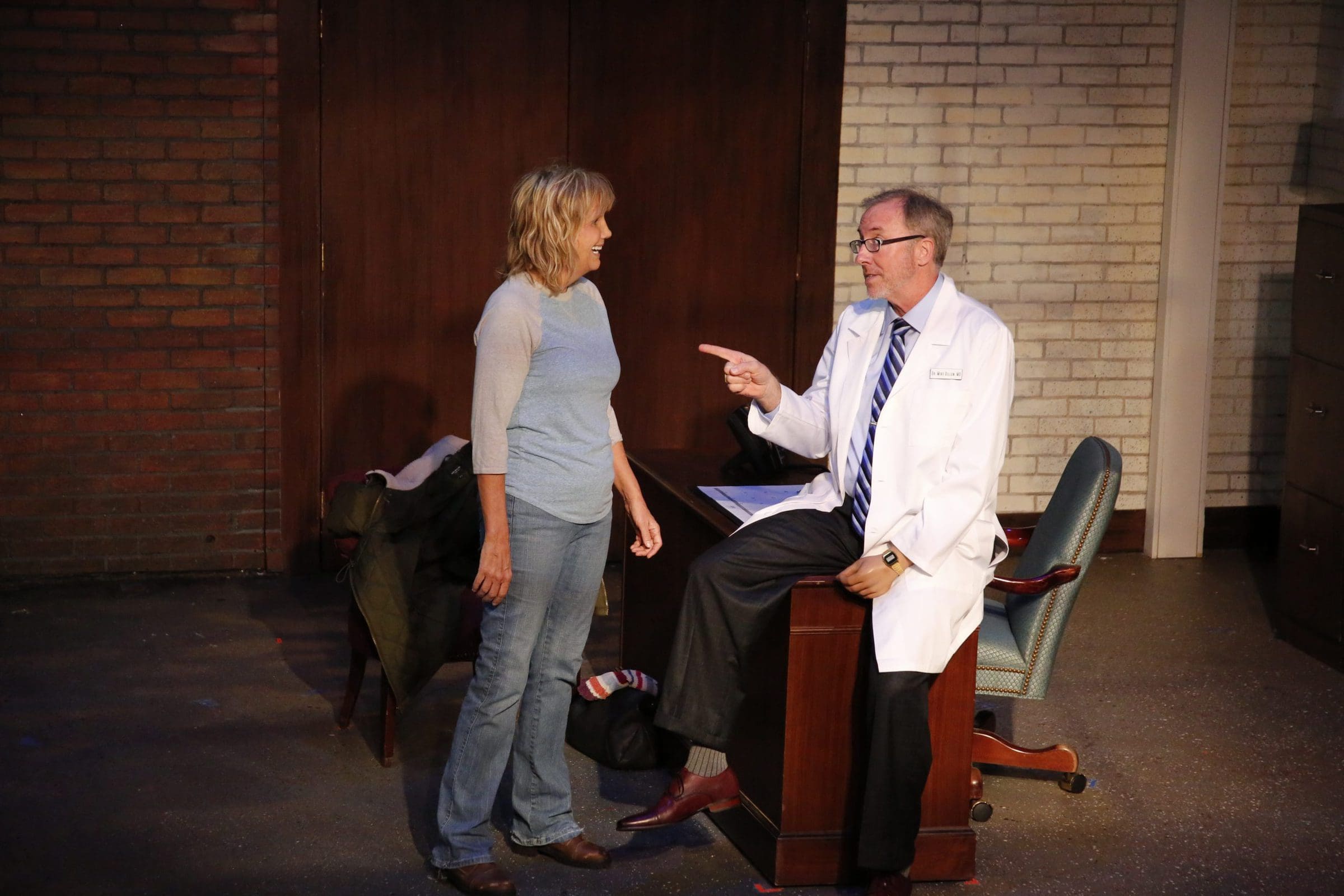

Margie shames Mike into an invitation to his birthday party at his home in Chestnut Hill, several miles and a T train ride away. When the party is canceled, Margie is convinced that Mike’s lying to her. She shows up anyway. But Mike’s daughter really is ill and the party has in fact been called off. Kate (Tamiya McClem), Mike’s young, African-American wife and a literature professor at Boston University, first mistakes Margie for one of the party-rental crew. As soon as Kate realizes her mistake, she invites Margie to stay for wine and cheese, much to Mike’s dismay, and even eventually offers her a job as their daughter’s babysitter.

The disparity of their worlds is apparent when Kate apologizes to Margie for only being able to pay $15 an hour for babysitting, which, for Margie, would mean a doubling of her Dollar Store starting salary. For all of Kate’s empathy for the poor, she simply cannot understand what it means to be hanging on by a thread.

In one scene that brilliantly demonstrates the uphill struggle of poverty, Margie tells Mike how her car was repossessed because she missed a payment to cover a dentist’s bill, caused by a cracked tooth she got trying to save money by eating peanut brittle for dinner. She had no insurance so the crack led to an abscess and a bigger bill.

In other words, when you’re scuffling on the margins, as so many Americans are today, one bad break often cascades into bigger ones.

The title of this consistently engrossing play is drawn from Margie’s description of the Mike she knew in girlhood, “He was always good people,” but when it comes to measuring true goodness, every human being is a wild card: They can flat-out surprise you sometimes.